Originally written Sept. 2011

Most Thursdays, I volunteer at the Jac Smit Urban Agriculture Library at the FoodShare building in Toronto, Ontario. A few weeks ago, I came across a very interesting document.

Garden Homesteads for Cuyahoga County, by Bernard S. Edelman (1942), offers a glimpse at a unique suburban planning concept for the region surrounding Cleveland, Ohio. I say “unique” because I have yet to come across any other similar planning reports from that era. The first paragraphs of Edelman’s report read like many publications today:

“Idle land, idle time, inadequate diets — except during boom times city dwellers see these conditions about them all too prevalent. Why did such a sate of affairs come about? How did America in a century and a half change from a county of rugged, self-sufficient farmers to a county where the great majority of the population is separated by a complex distribution system from the land, which gives it its sustenance? The economics of this situation has long been studied by socially conscious writiers and thinkers.

“The recent depression enormously stimulated the thinking upon this subject and hundreds of books, pamphlets and articles have been written. Considering this abundance of material it is not necessary that this report attempt to analyze in detail the underlying social and philosophical concepts of ‘a return to the land.’”

Edelman goes on to explain the context of Cuyahoga County and a brief history of the “garden homestead.” He links garden homesteads to the tradition of allotment gardening but also points out some identifying characteristics specific to garden homesteads. First, the homesteader “does possess a principal outside income from an established source;” second, the homesteader raises “produce principally for home consumption rather than for sale;” and third, the “presence of some sort of community plan and development” (Edelman, 1942:3). Edelman goes on to discuss some of the advantages of successful garden homesteading, such as semi-rural living (fresh air and sunshine), a healthier diet, skills development and education, exercise, food security, sense of community, and the satisfaction gained by productive work.

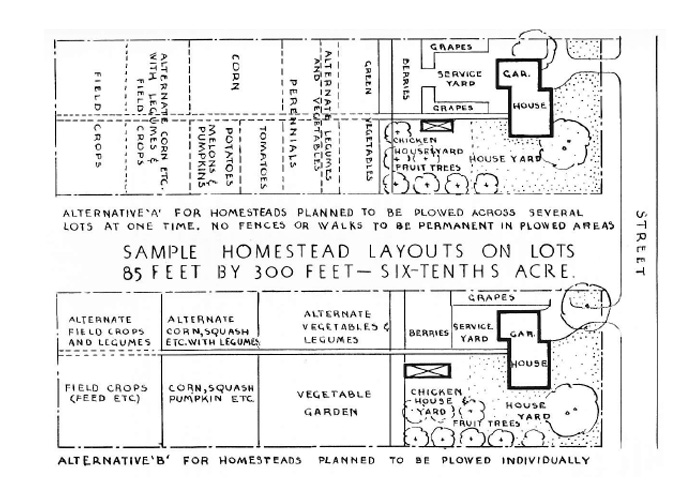

Through surveys of county residents and site conditions (land cover, fertility potential, etc.), Edelman concluded that there was sufficient evidence to justify at least two or three developments immediately upon publication of his report. The factors of transportation, shopping facilities, schools, utilities, land cost, and taxation would all be weighed when choosing a site for a new garden homestead community. Regarding finance, Edelman researched other similar communities and found three characteristics to be particularly common. First, there was a preference for lots one acre or less in size; second, a price of $4,500* or less for the house and lot; and third, consideration of the many possibly ways to fund homesteads — all relative to the income levels of the residents.

References:

Edelman, Bernard S. (1942). Garden Homesteads for Cuyahoga County. Regional Association of Cleveland: Cleveland, Ohio.

*$4,500.00 in 1942 had the same buying power as $63,632.61 in 2011. Source: http://www.dollartimes.com/calculators/inflation.htm